Curios at La Scala

Curios at La Scala

Cooked to perfection

If, for some inexplicable reason, you found yourself being catapulted back to a late-sixteenth-century theatre, you would discover a performance very different from the one you would see today.

Theatres were built of wood, lit by candles and heated with braziers; at the back of each box, every noble family kept a cook, ready to cater to their whims. So it is quite understandable why theatres quite commonly caught fire. This was the end that the Teatro alla Scala’s “ancestors” met: first the Salone Margherita, then (twice) the Regio Teatro Ducale. It was after one of these fires, that the box owners, the great noble families of the day, decided that Milan had to have a its own great municipal theatre, no longer a prerogative of the nobles but of the people, too.

So, on 3rd August 1778, on the degraded area of the Church of Santa Maria della Scala, began the story of the Teatro Grande alla Scala. And this time, it was finally built of bricks and mortar.

The farsighted architect

When the Teatro alla Scala was built its surrounding context was very different from that of today, with Piazza della Scala only being created in 1858.

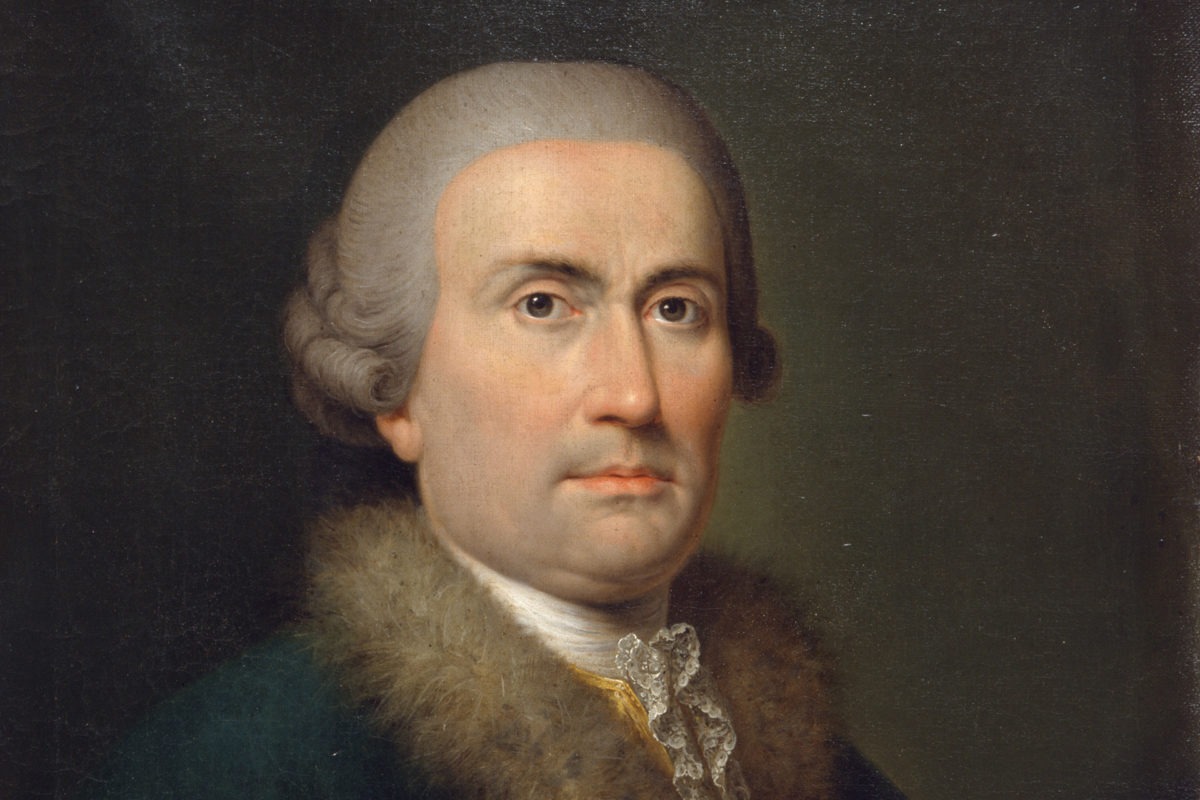

The design of the Theatre is in fact best admired from the side, rather than from the front, a perspective clearly visible in Angelo Inganni’s painting exhibited in the Museo Teatrale alla Scala. The result obtained by the architect, Giuseppe Piermarini, did not please everyone. The philosopher, Pietro Verri, for example, stated that “the façade of the new theatre is very beautiful on paper, and it even surprised me when I saw it before work began on it; but now I almost dislike it”.

Verri’s unfavourable opinion was due to the porch for the carriages, a solution that Piermarini adopted to provide the façade with some depth, which would otherwise have been impossible in such a narrow street. However, his choice proved farsighted: in the mid-nineteenth century Piazza della Scala was opened and the architect’s decision appeared quite prophetic.

The anatomy of a Theatre

Today, La Scala can seat a total of 2,015 people. Originally it had five tiers of boxes, but in 1909, the fifth tier was transformed into the first gallery with the removal of the separating walls between one box and another.

The second gallery, just below the vault, is the famous “loggione”, where the keenest opera fans head because it is the part of the Theatre in which the acoustics allow the listener to hear the singers and the orchestra best.

The boxes are not all the same: on the second and third levels there are fifteen in which traces of the original decoration can still be found, and which in some cases dates back to the intervention of the scene designer Alessandro Sanquirico in the early nineteenth century.

Let there be light

When electric light came to Milan, the first public building to be illuminated by the Edison company, was the Teatro alla Scala, in 1883.

Today we think of the theatre as a silent, magical, twilight place, and we no doubt find it strange to read on a poster of the time describing the Teatro alla Scala as being “floodlit”.

But the central grand chandelier did just that, thanks to its 383 bulbs. The chandelier that we see today is a faithful copy of the original, which was destroyed during the air raid of 15th August 1943.

Le Jeux sont faits

In eighteenth-century theatres, La Scala included, each box belonged to one of the noble and bourgeois families. They were allowed to decorate and furnish their boxes according to the own personal tastes; they could also rent them out, sell them or bequeath them.

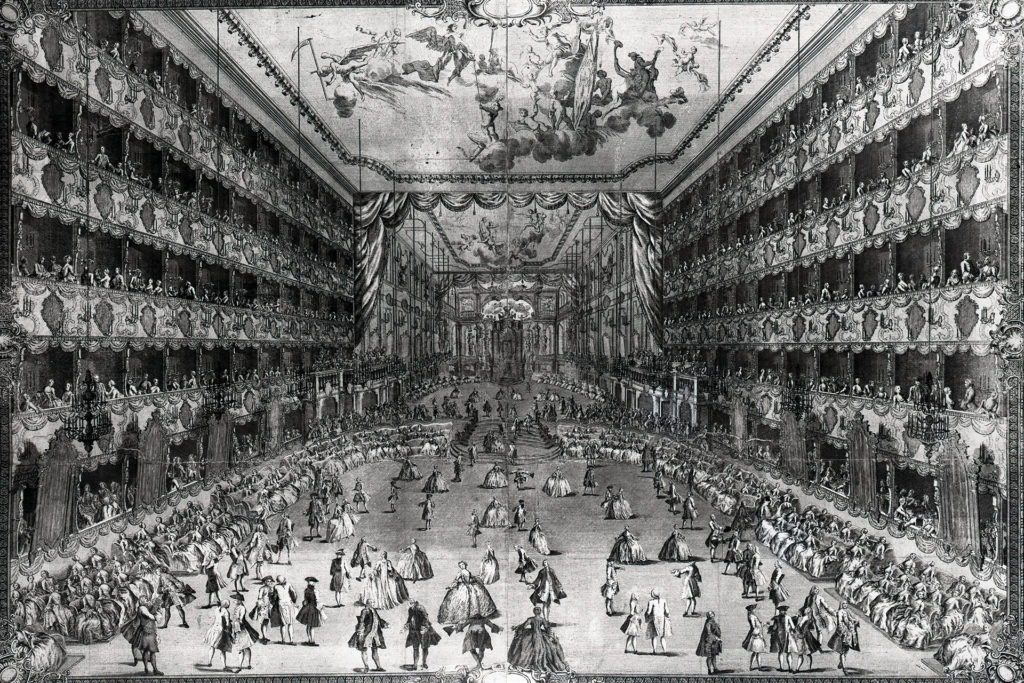

The seats in the stalls were moveable and theatregoers had to hire them if they wanted to sit down. The reason for this was that the Teatro alla Scala was often used for balls, masques and even horse tournaments. It is difficult for a modern spectator to imagine the atmosphere of the time, with the smell of food and smoke, the confusion and the lights.

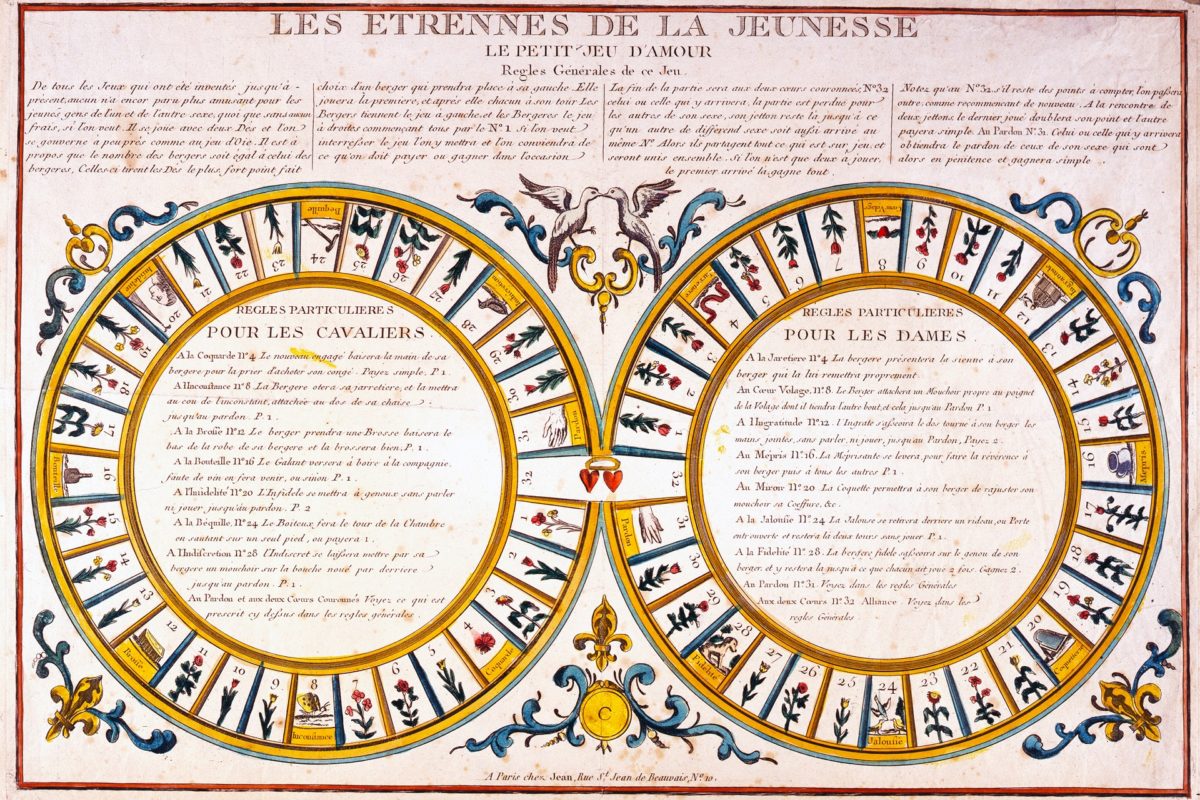

In the hallways of La Scala, it was common practice to gamble. One illustrious guest at the roulette tables was Alessandro Manzoni. According to contemporary accounts, it was the poet, Vincenzo Monti, who “rescued” Manzoni from the bad habit he was acquiring by exclaiming: “We want to write beautiful verses, yet you continue to act in this way!”.

Long live la Scala!

On the night between 15th and 16th August 1943, the Theatre suffered considerable damage during air raids carried out by the Royal Air Force.

Reconstruction began with an unusual concert amidst the wreckage, the orchestra seated in front of the curtain and the audience on ordinary chairs. The Teatro alla Scala was rapidly rebuilt and on 11th May 1946 it reopened in all its original splendour with a memorable concert conducted by Arturo Toscanini.

Toscanini is indeed responsible for many innovations of a musical, managerial and structural nature: he insisted on the creation of an orchestra pit (also known as the “mystic gulf” covering an area of 110m2), as well as the introduction of dimmed lights in the auditorium during performances, a new type of curtain, and the banning of encores.

Metamorphosis

In The Leopard, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa wrote: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”. During its turbulent architectural history, La Scala has seen two moments of important transformation.

The first was the reconstruction of the Theatre, carried out by Luigi Lorenzo Secchi, following the air raid of 1943. The second was the massive renovation work (2002-2004), conducted under the supervision of Mario Botta. The two architects, however, had one thing in common: the precise intention of conserving the past and the history of La Scala. So the vault, destroyed in the bombing, was rebuilt according to the same measurements and using the same materials (hard poplar) as those employed by Piermarini.

New nails were made copying the eighteenth-century nails found among the debris. During the renovation work that began in 2002, the carpet in the stalls was removed, along with the bombing debris that had been hurriedly buried under the stage, as well as the linoleum from the boxes revealing the eighteenth-century Lombard-style tiles.